A conversation with the photographer, Naoya Hatakeyama

Interview with Photographer Naoya Hatakeyama, 2010, Tokyo Japan

Robert Hutchison:

As an architect, my firm has been very interested in work that explores the edges of architecture, not just building buildings, but doing other things that are beyond architecture, such as installations, photography, different things like that.

Naoya Hatakeyama:

Including words?

RH

Yes, including writing. When I arrived in Japan, I began to meet architects and artists whose work in some way occurs at the edge of architecture. Meaning architects whose work begins to diverge from architecture, and artists whose work in some way might address the topic of architecture. So in the case of your work, it was not that you were addressing specifically architecture, but I thought that there were some interesting conversations and discussions that you, especially in your writings, and the way that you relate to your photography that I thought was very interesting. So I have been meeting many people, and I realized that if I am having these conversations, it would be great to record them and assemble them as a record of interviews that talk about this issue related to Japan. So I have interviewed almost 15 people from varying backgrounds, some very well known such as Atelier Bow-wow…

NH

Tsukamoto-san …

RH

Yes, and I am scheduled to interview Kengo Kuma, Klein Dytham, and numerous others, as well as photographers and artists. But also some people not as well known, both architects as well as artists. As I do more of these interviews, I am finding my discussions with artists and photographers to be particularly interesting. Your work is especially of interest to me. Over the last few months, I have read as many of your writings as possible … Lime Works, Under Construction, Scales, … And I have assembled some questions that start with photography in general, then go into your work, and into architecture. But I am finding that the best interviews are those which tend to be not so formal, they are just conversations. So with that, I thought I would start with asking a question which I have not seen addressed in previous interviews and writings, and then we will just see where things go from there. So my question is, what attracted you to photography? I have heard why you have done what you are doing with your photography, and who you have been inspired by, but I am curious what brought you to photography?

NH

Well, that answer is both very simple and very complicated. The beginning of my photography was the encounter of my photography teacher in the University. I was a student of Tsukuba University in the beginning of the 80’s.

RH

So you did not enter as a Photography major?

NH

No. I wanted to study art, of course, but mainly in printmaking and painting at that time. But I met my teacher, who’s name is Kiyoji Otsuji, and I decided to study photography under him, because his talk was very interesting.

RH

What was so interesting about it?

NH

Well, photography is a very easy thing. So any person can take photographs. And usually we use photography to communicate with people, or to express your inner space, or idea, to the outside. Anyway … his style of teaching was completely different. He taught us that the nature of photography means … photography and the word ‘outside’ and ‘us’, there is a composition of the word, which is, you can divide the words into two things. The word ‘inside’, and the word ‘outside’, the word ‘outside’ means the physical world, the word ‘inside’ means idea, or sensation, or thinking, or mind. And if you put the photography as a medium just in between, we can …

RH

So you mean in between the inside and outside?

NH

Yes, which means medium! (Laughs). Then we can have a new dialogue, maybe, between these two things. So, without photography, the word ‘outside’ is sometimes just a reflected image of the self. But if you insert that medium in between, then sometimes you can find the very realistic feeling of the outside world, which is very physical. For instance, you cannot take a photograph of an idea, you cannot take a photograph of somebody’s name, or somebody’s thinking. The other photographers working at the time were making an effort to express something, their ideas. They even tried to express somebody’s … not name … mind maybe? But my teacher was completely different. I was young, and I had been having the feeling that the world through ideas and people’s names, and the mind, sometimes it was so boring, and I would get tired of it sometimes. So his way of teaching was completely different. For instance, he said to me, you can take off any explanatory stuff from your photograph, everything. So I just tried to make a photograph without thinking anything. It’s like automatism, like an experiment of surrealism in the beginning of the 20th of France …

RH

Similar to the notion of automatic writing?

NH

Yes, like automatic writing! So, even if you take a photograph in that way, you can have a perfect image. From that perfect image, you cannot see anything connected to somebody’s inner world.

RH

When you mean somebody, you mean the person taking the photograph?

NH

Or ideas, or anything. Nothing. This is just a shadow of the physical world. And sometime that kind of photograph looked very attractive to me. And so I got interested in practicing that in my school days. So it was the dominant way of making art in the beginning of the 20th century actually, especially in France and Europe. You had Expressionist, but at the same time you had anti-art movements, such as Dadaism, and Surrealism. My teacher was a member of one artists group called Jikken Kobo, which consisted of composers, critics, painters, graphic artists, and sculptors. It was founded in 1951, 1952, I can’t remember. And the theoretical axis of that group was a poet named Takemitsu. He was a very very important person in the avant-garde art history of Japan. And he was exceptional because he had been continuing correspondence to Andre Breton and Marcel Duchamp. He died in 1979. At that time, my teacher was in my school. So my teacher and Takebutsu were working together for more than 20 years. But that’s the beginning of my photography. I knew that there were many kinds of photographs, and many kinds of photographers, but for me that was the only interest in photography in my school days.

RH

This is interesting, because one of the questions I had written down for you was if photography for you is about expressing yourself in any way? It seems like it started out as not …

NH

Well, in a broader sense, I can say that myself is expressing something, even if I take a photograph of nothing, it’s a kind of expression, of course. But, I think it’s a topic of generation maybe. After the war in Japan, I think there was a big tendency of skepticism, suspicion. There were many, many experiments in the field of art. And the characteristic of that movement is how you can vanish yourself from your expression. If you have object and subject, in traditional art the subject was very important, but in avant-garde art the subject became a big question. So, when I was young, there was an air like that around me. So for me it was quite natural to focus on photography under my teacher.

RH

Is there a difference between photography as documentation versus photography as an art?

NH

Well it can be both, or either. At least until the 80’s. But now in 2010, I have no idea. Photography can be documentation, I’m so doubtful.

RH

So doubtful of ..

NH

The nature of photography has been changed, because of the digital technology. The authenticity of photography is a big question now. Because of that, the reality of photography is changing. Authenticity in photography in the 20th century was obvious, until the 80’s. So the reality of photography was stable. So we could enjoy many many games on that basis. But authenticity is a big question now. So the form of reality changed accordingly. So, the lure of many games are changing accordingly. In the 21st century photography, I mean the future of photography, I have no idea what it will be like.

RH

Do you think that is a good thing?

NH

Yes.

RH

I think of photographers like Andreas Gursky, whose work is completely digital now. I myself have become interested in how it is changing in the way you described.

NH

Yes, but there is still the reality of photography. No one knows what authenticity is anymore, but there is still some reality in Gursky’s work.

RH

Let’s discuss some of your writings. I think that your writings are very beautiful, and I myself think that there is a complement between the two, between what you write and what you photograph. My own personal connection to this is that I appreciate how the two relate to each other, and I begin to think that without your writing the photographs are not satisfactory; that the writing supports the photographs, and the photographs support the writing. I am curious if you feel this way, and perhaps a broader question is how you view the role of writing to your photography.

NH: A very small child, like a baby, does not know the difference between a sign and a figure. When he writes something on the paper; after the baby practices many drawings, he will know the difference between sign and figure. The sign means words of course. I think we cannot see things if we don’t have words. Which is bumsitska, I don’t know how to call it in English. Anyway, the word is a tool to divide the world …

RH

Words are tools to divide the world?

NH

Yes. Which means, words create the world. The world is created by words. So words and visual things are strongly connected. Sometime you can use words to express something, or sometimes you can use figures, or shadows to say something different.

RH

This makes me think of the expression in english, a picture is worth a thousand words. And what you are saying is that this is not always the case.

NH

Not always! One could also say a word is worth a thousand pictures!

RH

That’s great, I like that! I will bring that one home with me.

NH

So, words and images are different things, I know this. But they support each other. And if we don’t have words, we cannot see the world, we cannot even have the image.

RH

I see that very clearly in your books.

I am very curious, I had read that you worked with Joseph Beuys early in your career.

NH

Oh yes!

RH

What did you get out of that experience, if anything?

NH

It was completely by chance. At that time, I was just a young man, who has no skill of making films. After I graduated from my school, I had no work, so I asked my sempai, my friend, who was already working in Seibu Depato group. At that time, Seibu was very active in promoting themselves as a cultural leader in the consumer society of japan. Consumption and culture is what was mixing. It was the 80’s. There is a word, Sobikunka, it means consumptive culture. To buy a thing is attending to the culture, that was the era. And Seibu group had great power in culture. In many department stores, they put tv monitors up, and they created their own programs on those tv monitors. So my friend was working in the section of the department store that was making these tv videos, for instance the image of sakura blossoms (cherry blossoms), or in autumn, you would have a big image of a full moon on the wall. And of course, in the beginning of summer you would have a beautiful image of the blue sea and sky. At the same time, sometimes they would make a special video of interviews, because in the 80’s the New York art scene was so powerful. So we had Laurie Anderson, and Nam Jun Paik, and many many stars, who came to japan and they would have an exhibition or performance, which videos would be made of. One day, my boss heard that Joseph Beuys was coming to Tokyo, and that he would open a 1-month show at the museum, the museum which is run by Seibu Depato. Can you imagine, there was a museum inside the department store! It was the only museum which showed contemporary art at that time, in the beginning of the 80’s. Of course, we had many museums of modern art, French impressionists, avant garde art from the beginning of the 20th century, but as far as contemporary art was concerned, we did not have any large museums which showed the art of our contemporaries. So Seibu museum was very famous, and it was located inside the department store. Anyway, we were very excited because we had Joseph Beuys from Germany coming to our museum. And Bueys asked me if I could be a director. I was 26 years old! I was so amazed, but at the same time for me it was so challenging. So I would follow him for 8 days with my video crew, and after he left, I worked for a long time in the studio to edit the video tape.

RH

So you were actually filming him?

NH

Well, the camera man was different, but I was the director. But it was not my artistic practice, it was just by chance.

RH

So did he, over 8 days, was there any influence from him on your later practice?

NH

Yes … many things. I felt the fever of people in art schools, and around museums, and the fever of the art world in Tokyo. Now it’s gone. To talk about him and his work is too much for me. Last year there was an exhibition of his at Art Tower Mito. They made many interviews with people who were there in 1984, like Yuko Hasegawa from the Museum of Contemporary Art, and Hare Oishiro, a famous critic who died recently, and the digital artist Miyaji Matotsa, the artist who uses a digital counter. His large work is just in front of the Roppongi Mori museum.

RH

So let’s switch the discussion to your specific work. Much has been written by others as well as yourself regarding how much of your work has a focus and relationship between dual themes of rural and urban, city and countryside, man and nature. But it seems like your work of late is starting to focus much more on the city. I am curious, why do you think that is the case, maybe because you live in Tokyo, why is it going that direction, or do you even see it going that direction? It is interesting for me to look at your Lime Works project, and the discussion of the rural and the inverse relationship to the city. But lately the work that you have been doing seems to be more exclusively to the city.

NH

Well, I still work in rural areas. But I don’t have books that document this work recently. For instance, last year and this year, I was working in northern France on Slag Heaps. In 2004, I was in the Ruhr area of Germany to record the demolition of buildings of an old coal mine. In 2003, I was also working in southern France on a steel factory. In Tokyo, yes of course I have work here, but I still work in rural areas.

RH

Do you think that this will always be an interest for you, a balance of working in both conditions?

NH

Yes, because real nature, the real city, is very difficult to be taken in photographs. So the smart method … (does not finish sentence). At the beginning, you were talking about your own interests, your interest in the edge of the field, you mean the edge of architecture in your case.

RH

In my case, so far, yes.

NH

I think it is the same thing for me. Because if you like to take a photograph of the city, sometimes it is better to take something different from the city. So sometimes it is better to make things itself; if you like to take a photograph of the city, sometimes it is better to take a photograph of the edge instead.

RH

This is quite a nice thing you have said, can I use it for my own?

NH

If you take a photograph of nature; if you take a picture of this center, it is very hard to describe something. But if you describe this area, maybe you can make a figure of nature in a sense. So many people who are interested in working on cities, they take a photograph of suburbs, or industrial areas. Or I can say that man and nature, this is … two things countering each other. But if you, there is, one thing, luck, just nature, maybe with that man, the notion of nature does not exist. Without nature, maybe the notion of man does not exist. So it is always … things come from here, a dialogue of two things. I am always working here. I’m sorry, my vocabulary is very limited!

RH

I don’t think so, but if you are more comfortable please speak in Japanese!

NH

Yes, I think I might be able to express myself more elegantly.

RH

There is a book that I have had for a number of years called ‘Field Trips’, it documents photographs of an industrial complex in Germany. The photographs are taken by the artist Robert Smithson, and the photographers Bernd & Hilla Becher. It is a fascinating book; the Bechers took Smithson to this industrial complex; the book has the photographs that both took. Of course, the Bechers photographs are beautiful, large-format images documenting the architecture on the site. But Smithson’s photographs are of dirt and the ground, using a small instamatic camera.

NH

Yes, I think I have seen these black & white photographs taken of industrial places in Germany by Smithson.

RH

I guess when I first started looking at your work, in particular the Lime Works and the accompanying writings, what I found very interesting was that the photography had a nice relationship to the Becher’s work, but the writing I thought was very Smithson-like, a very interesting relationship topically to his discussions concerning entropy and nature. I was curious, are you familiar with both of these artists, and what are your thoughts regarding their works?

NH

The influence of the Bechers was great to Japanese photography, for the world of photography. Everybody knows their works. I think many many photographers have been influenced by their works.

RH

Especially the Dusseldorf school, but what you are saying maybe Japanese photographers as well?

NH

Yes. The use of typology, but also the use of a large-format camera, provided a strict rule of making pictures. And the appearance of the photographs, or the method in which they were presented – when you went to see their exhibitions, their photographs looked like sculptures. The way of presentation was very important. They were great artists. And Robert Smithson … I knew of his name when I was a student because he was a very important sculptor at the time, land art was very famous among Japanese students – Spiral Jetty! But I think it was in the 90’s, there were many exhibitions on Robert Smithson in the US and Europe. I had one catalog of Smithson’s photography works, by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the book of his writings were published. At that time, my Lime Works were published, in 1997. So when I showed my works in London, I did not imagine anything about Robert Smithson. But museum curators, galleries, many people asked “how do you see Robert Smithson’s work”? It was so fresh to me – until that time I did not really think anything about his work. But of course, many interesting things he was thinking. But I did not know why I was working on Lime Works.

RH

Smithson I find a little bit difficult to read, I am not the most philosophical person, I am simply a practical architect. But I do pick up his readings once in a while, and when I read your Lime Works, it was interesting to me how you talk about the connection and relationship of the inverse of the material being removed from the site, and being placed into the city. When I read Smithson, he talks about entropy, and he implies that there is no cycle; things just keep changing, and things never return to an original position. What do you think about this? Do you agree with this, or do you think things run in cycles? For example, the Ruhr valley project that you mentioned in Germany, where you document the demolition of the buildings. It struck me that there you were documenting buildings that are returning back to earth, but with Toyo Ito’s Mediateque you are photographing a building being constructed from the earth. I don’t really know where I am going with this, but it seems that this is representative of a cycle, yet Smithson talks about it not being a cycle; everything continues and breaks down.

NH

In my mind it is not simply a cycle, or just the changing. Maybe it is changing, and coming back over itself, like this (draws a coiling spiral).

RH

I thought you were going to draw a spiral jetty, but actually you are drawing a coil!

NH

Yes, exactly. It’s a coil, it overlaps. So from this point, the landscape looks the same. But something is already different.

RH

And the difference between these two points is time.

NH

Yes. From this side it looks like a cycle. From this side, it looks just changing.

RH

You are drawing like an architect.

NH

Hmmm.

RH

This is why I do these interviews, because I can’t figure this stuff out by myself.

NH

We can never go back to the past. But the scene looks the same. Many many things look the same, but they are not.

RH

Speaking about these two projects; I have always been interested in deconstruction; the artist Gordon Matta-Clark is one I have always been interested. So I was interested in how you documented this large mine facility in Germany. But then you photographed the construction of Ito’s project. I began to wonder, with photography, what is interesting is it freezes time, it stops the moment, and I began to wonder, is there any difference here? With photography, if something is being demolished and being taken apart, and something else is being constructed, when you photograph them they are at the same point. Do you see a difference between photographing something that is being taken apart, and photographing something that is being constructed?

NH

Hmmmm …

RH

Am I getting too philosophical here?

NH

I think I can show you the difference in my photographs … (disappears for two minutes, returns with photograph book ‘Atmos’ which shows the French deconstruction project).

RH

For myself it was interesting to look at these. Obviously the ones which are where the building is actually falling down have a different atmosphere. But these, the Imato Dori and Ito, they seem very similar.

NH

My explosion pictures … these pictures were taken with the same equipment. I set up from a distant place while shooting, I used a radio controlled camera.

RH

Using a field camera?

NH

No, a Nikon 135. (F5) It’s too dangerous to be close up with a field camera. Film; I don’t use digital … at the moment. So both of these photographs were taken with the same equipment. The looks are similar. Something is breaking. But this is for making cement. So you can say this is the beginning of a building!

RH

That is interesting, so what you are saying that this point is here, and that point is there, but they look very similar.

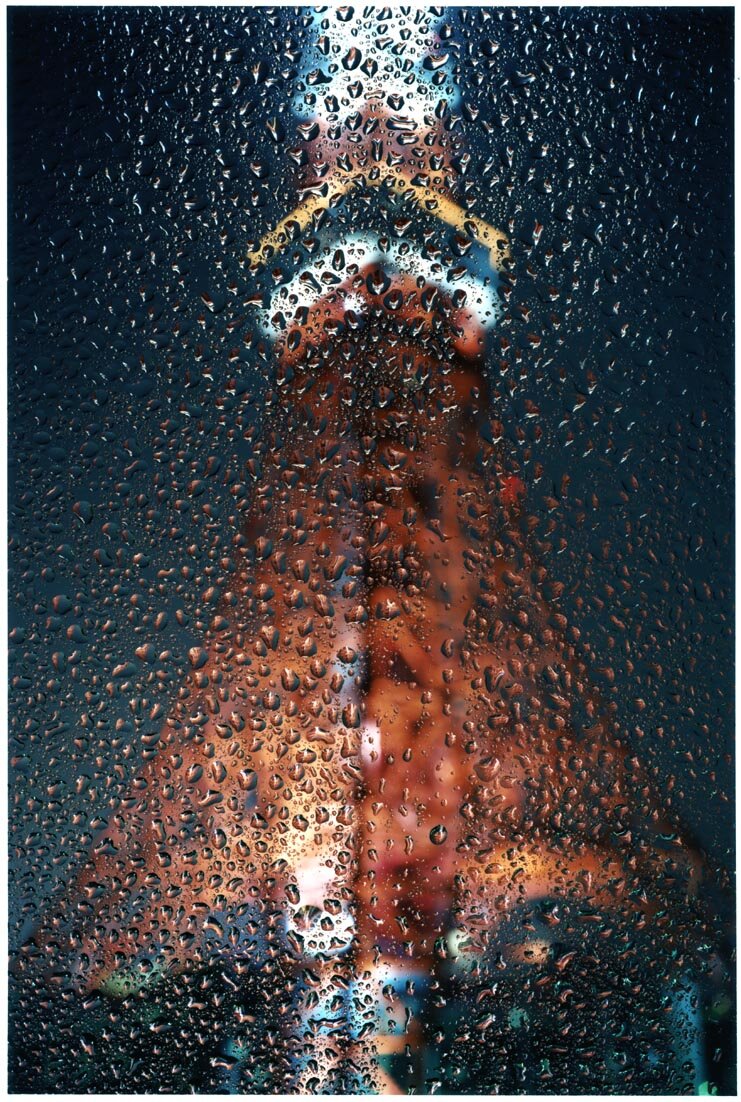

So I am all over the map. I saw your ‘Slow Glass’ images at the Taka Ishii gallery. But I have not seen the maquette/light box series. Both of these series are very interesting to me, because with the slow glass series you are creating a new ‘camera’, whereas the light box series are using a different way of presenting photography. How do these relate to the rest of the work that you are doing? Are they more experimental, or do you see them as tied in to the same investigation?

NH

That is a very good question. Because that is a question of consistency of artistic practice. Viewers always expect a consistency of work from one artist. Some artists are repeating only one thing every day. Like Roman Opalka from France, he is just drawing the same number every day, and he makes a self portrait every day, for 45 years or so. It is so wonderful in a sense, but I am not the kind of artist of that type. My interest is having, or creating, my own vocabulary of photography, as many as possible. So from my young days, I was always trying to do that. In 2002, I made a one-man show in Germany. After the hanging of all of the works, to my eyes it looked like a group show, not a one-man show. I had many different works. So my impression was, “oh, this is a kind of group show!”. And I enjoyed that. So maybe I am trying to make my vocabulary richer. And maybe I was trying to write one poem, or one short story, with those vocabularies some day in the future, at the end of my life.

RH

These two series seem, even though they focus in some way on the environment, their focus seems very different than the other works. It seems that the light boxes are about lightness and darkness, and the slow glass photographs seem like a different way of looking at something using a different way of photography.

NH

Well, the first slow glass image was created in Britain in 2001, while I was a resident artist in the town of Milton Keynes. I was invited as a resident artist there for 4 months. I think I can bring the catalog … this book.

RH

Oh, this is where you stood high on a ladder on photographed over fences down into yards of single family homes in Milton Keynes.

NH

Yes. I was inspired by a science fiction novelist named Bob Show (?), I believe an American author. After coming back to Tokyo, I used that same camera to make a series of Tokyo landscapes.

RH

That’s what I thought, that the slow glass images in the show were Tokyo.

NH

Yes. I used a vertical format instead of landscape. The slow glass in Milton Keyes, the photograph is simulating the windshield of a car. I drove a car and took photographs.

RH

It is very interesting to me that there is some experimentation that is happening with technique here that is different from your other work, which I appreciate.

NH

This is a book called ‘??’ steel company in southern france. So I made a book like this. It is juxtapositioned, man and nature. You can change the pair as you like, as you see fit.

RH

What interests you about architecture?

NH

Materials. I trust architects because they are struggling with idea and material. They are in the midst of conflict of idea and material all of the time. People who use words and images, sometimes they are losing something very important, a physical sense. If you drop something, it drops like this. An architect knows this. If you build something like this, maybe it will fall down! An architect knows this.

RH

Did you see or hear about Junya Ishigami’s sculpture at the Venice Bienalli?

NH

I did not. But I saw his huge balloon project.

RH

At the Venice Biennali, he constructed a structure with super thin carbon members. But after 2 hours it fell down. They tried to rebuild it, but they could not.

NH

His balloon was fantastic. It was made I believe of aluminum. It was so large, like 10 meters in all dimensions, it was like a floating rock. But it had helium gas inside it, so it was floating inside the space. One person could move it with their own hand. One man was guarding the balloon, he was in charge to make sure the balloon would not touch the wall.

I know Mr Toyo Ito personally. He is always saying “building architecture is a kind of fight with materials. People who know architecture looking at photographs or through words do not know this. Only architects and carpenters, the people who work on construction sites, they know this”.

RH

In your writings you talk a lot about the very people who are involved with these things, like the Lime Works, you talk about the people on site, or Toyo Ito’s Mediateque you talk about the ship builders who come from your home town. I appreciate this connection to people. With your ‘Under Construction’ essay, what I appreciated what that there were two independent essays, one by you and one by Ito. Instead of the two of you having a verbal conversation, your two essays served as a conversation. In your essay, you came to architecture from a very broad perspective, whereas Ito was starting from architecture and going to a very broad perspective. The two essays had an interesting relationship, and the interesting meeting point was the topic of what you termed the “invisible information environment”. I never thought of it this way, but you called it the ‘new nature’, and we are the aliens, coming out of Ito’s Tarzan reference. The question that I still had after reading these essays, was where can architecture play a role in this new nature? You talk about Ito’s building as a ship, but it is difficult for me to think about how architecture is really going to play a part of the ship in this new information environment.

NH

Architecture continues I think. Even architects are using digital technology, like computers. Actually, Toyo Ito is making buildings completely by computers. For instance, his opera house in Taichun, his new project, the wall is unbelievable, like a wave. It is possible because of the use of the computer of course. But at the same time Ito is always a man of physicality. So he is keeping a balance between this tangible and intangible condition; or you can say between this visible and invisible. His ship (laughs), even he uses a very sophisticated technology. But he is always touching the wall, he knows the rule of the physical world. If he loses this sense, then the building will be broken, like Ishigami’s sculpture. This is forbidden for architects. And so he is so careful. And I think he is enjoying this balance. Invisible architecture, or intangible architecture, something that you cannot feel, will be possible in the future. But as far as we human bodies exist, there must be some aspect of materiality, or physicality.

RH

If you lose material and touch, then it is just the mind? We don’t need the body anymore. It’s like the matrix.

NH

Yes. Of course, the next question is what our bodies will be like in the future. If our bodies change, architecture will change. If we don’t feel our body any more, if the body can be intangible or invisible … it is possible I think?

RH

Someone mentioned to me that there is a professor in Tokyo who is working on trying to make people invisible. Have you heard about this?

NH

Yes, Transparent Man! It is a kind of suit. You have a camera somewhere, and a suit like a screen, and an image from the back, so you can be transparent. But your body is still there!

RH

Ok, just a few more questions. Let’s talk briefly about Tokyo. I had some drinks with a Japanese architect friend of mine, he told me that whenever his foreign architect friends come to Tokyo, he wants to show them to all of the famous buildings, but all his friends are interested in are the strange and crazy things in Tokyo, the crazy exterior staircases, the complete lack of zoning conditions. And I profess that I am interested in these things as well. Speaking for myself, as a foreigner, what seems so interesting about Tokyo is that from our sensibility there seem to be no rules, or no way for us to understand an order, especially coming from a city like Seattle, which consists of many monopoly houses row after row. So Tokyo is very exciting to us, what we see is a lack of restraint, and this translates to the notion of freedom in our minds. I thought of your Yamate Dori project; what are your thoughts about Tokyo? Are they similar to our own thoughts?

NH

I myself can see why you see randomness, and disorganization of street structure, telephone lines, and so on. And photographers from Europe are very happy when they come here. From their work, we already learned something. The view from outside. But the view from outside of Tokyo … we already learned that. So if I were a guide for the architect from overseas, maybe I can take them to the places like this. Because I learned this already. And my photographs of Yamate Dori … (pause) … I did not think anything about this, of nationality, of difference of nations and cultures. But I agree with you, this disorder and the mish-mash of Tokyo is very attractive. But the fish in the water maybe does not know if he is in the water or not. It is something unconscious.

RH

The fish does not know what is outside of the water …

NH

Or even if he is in the water! If you are living on the inside, you cannot notice such things. If somebody from outside points to something as unique, we notice this finally. But until that time, we did not really know this. And actually, it was an awful thing to show these disordered mish-mash ugly things to foreign people. And so we have been trying to build “a beautiful architecture”, modern buildings like Europe and America, to welcome people from overseas. But since the 70’s and 80’s, it is a very new thing, because people actually enjoy the ugliness of Tokyo from this time. To my eyes, it looks like a very new tendency. For instance, in the Meiji period and the Taisho period, no Europeans or Americans came here. It was cool, hip, it’s enjoyable now. Small houses, and tiny streets of Kyoto. Potted plants everywhere on pedestrian ways. My Yamate Dori … I don’t think that this has something to do with this. I think I can give you the text that I wrote about Yamate Dori photographs in English.

RH

In one of your interviews, I think someone asked what is photography to you? And you answered that it is something that produces the future. Could you explain what you meant by this?

NH

If I answered that question now, my answer would be different. At that time, I was thinking about the digital/analog debate. I was always asked, why do I use film cameras? I’m so exhausted by that question! I was talking about the time lag. If you make the journey a very long distance to somewhere with a camera, you put the roll of film in the camera, and then you take photos, for example for two months. The first day, you take one picture. But you can develop the film in two months. So you need to wait. You need to wait for two months to see that picture. So, the picture is making the future. So a photographer’s practice is always like that. You take a picture, but you need to live until you see the photograph. Or, to see that photograph, I must live. Which means, I make the future. Otherwise there is no future. The present is here, all of the time. But nobody can say we have the future. We can only dream, imagine.

RH

But with the digital camera now, do we have a future?

NH

Well, our future is only one second or so!

RH

So what is your answer now, if I ask you what is photography? I promise this is my last question.

NH

I need a few minutes to think about this. What is photography …? (asks himself as he leaves for a few minutes).

(Returns with a book). This is a catalog on the architect Shirai Shoichi. Do you know this architect?

RH

I do not.

NH

He is a very outstanding architect in Japanese architectural history.

RH

Did you do some of this photography?

Yes, I was asked to do one or two photographs.

Do you know the NOAA building near Tokyo tower? Not far from Roppongi.

RH

It is interesting. I have seen a lot of architecture, but I have tried more to see everything rather than specifically architecture.

NH

So during your stay, what is the most favorite thing you have seen?

RH

Oh, I don’t know … but that is a fair question after I have asked you so many questions.

NH

People?

RH

No … not people. I have really enjoyed walking the back streets of all of the towns and cities that I have gone to, always at night, walking at night. Before this trip, I taught in Mexico City for the University of Washington. In Mexico City, you cannot walk around at night.

NH

Is it too dangerous?

RH

Well, you can walk around at night in some places, but you can’t walk anywhere you want. In Japan, I can walk anywhere I want at any time of day or night. It has been very interesting to see the towns and cities after most people have gone to sleep. This is probably the most interesting thing for me, to see these places at night.

NH

Do you walk, or bicycle?

RH

I walk. I thought about buying a bike, but it was so hot!

NH

Yes, it was incredibly hot.

RH

And it is interesting how seeing a city walking versus biking is a different experience. Do you know the musician David Byrne?

NH

Talking Heads!

RH

Yes. He wrote a book about bicycling through the city …

NH

With photographs?

RH

I don’t recall, but I think he does have some photographs. He talks about the difference between being on a bike versus walking. But anyway, I walked. But another thing that was very interesting to me was the difference in light in Japan at night compared to Seattle and the US. I have become fascinated by the standard fluorescent light fixture that occurs throughout all of the towns and cities. It took me a while to figure out the quality of this light. It seems like it is about light but also the darkness. You cannot have light without darkness, I think a very Japanese sensibility.

NH

Very good discovery!

RH

Yes, I think the notion of light and darkness is very nicely stated in “In Praise of Shadows”.

NH

Ah … Tanizaki. He talks about the joy of being on a toilet.

RH

So I am embarrassed to give this to you, but these are postcards of images of grain elevators. And on the back is text which talks about these buildings. These buildings are constructed with stacked 2×6’s all the way to the top of the building. Now they are being cut up and being taken down.

NH

In Japan, there was a project of anatomical analysis of one traditional japanese house by two artists. One is a photographer, anjai, and one is an architect, Suzuki?

RH

Ryuji Suzuki?

NH

The name of the project was je tai ken ba, which means absolute site. The photographer took each photograph of each time, of small details. It was done a while ago. Maybe 198?.

NH

(Looks through postcards). I like this kind of image. Somebody called it “deadpan”. No expression in the face. Deadpan. I like this feeling.

I have a plan to come in work in San Francisco, maybe next year. Because Sandra Phillips, the photo curator at the San Fran MOMA, is inviting me to make me work, in Silicon Valley. But I have no idea of what I should do, because Silicon Valley is famous for its computer industry. And it is not heavy industry. If you visit the place, you can see nothing. Just people working in front of computers. So it is a kind of invisible place. They already invited one photographer called Gabriel Basilico from Italy, he makes very static architectural photographs with large format. For a long time he has had a long career, he is very well done. And he has already done a lot of landscape photographs there, even in the town of San Francisco. So I cannot do the same thing. My interest is landscape and architecture, but he has already done it. So I need to do a different thing.

RH

Good, a challenge!

So, this is a book for you, it is a small publication that shows some of my firm’s work.

NH

Thank you! What is on the cover?

RH

The cover shows a detailed photograph of one of our Hole House projects. We did two of these projects, where we drilled into old buildings to create holes.

NH

This is beautiful!

RH

It was a lot of fun.

NH

This is still there?

RH

No. Two days afterwards, each of the projects were demolished. The second project is actually my own garage; afterwards we had a big party, and then built a new studio to replace the old building. We are very interested in projects that are about removal; about creating through subtraction, rather than the typical architectural act of construction. I suppose this is why Matta-Clark has always been of interest.

NH

Do you know the shape of this light? This is the light that is being reflected onto the wall from the sun?

RH

Yes. On this second project, we drilled the two side walls as well as the roof. In the end, you could not tell what was a hole and what was light; what was subtraction and what was addition; what was being cut through and what was being projected onto.

NH

So this is the projected image of the sun, correct? So when an eclipse happens … wow! A crescent!

RH

You are very right. We need to do a third one, and schedule it for an eclipse!

NH

Yes, and please keep it. You can invite people! As a work of art.

RH

The interesting thing about the first project was that we created it thinking about how nice it would look when it is lit up at night. So we put lights inside and lit it up at night, and of course it was beautiful. But what we did not expect was how the structure would emerge into the façade, so you could read the structure of the building as being one.

NH

Oh, ok! So this is a view from the outside at night?

RH

Yes. And this is from the inside during the daytime. But either way, with architecture, it seems like structure and skin are always separated, or overlaid, but in this image, they became one thing, through removing something. We did not think about this; for us it is really amazing to do something and learn something.

NH

Omoshiroi desu! Very interesting. I am always thinking about the difference of the sense of when you are inside of the room, and you look at the room from the outside. This is the same thing. But if you are in the room, everything is perfect. But if you go out and see your apartment, Tokyo Mansion, it is completely different. What is that difference? I don’t know.

Interview by Robert Hutchison conducted on September 24, 2010, at Taka Ishii Gallery, Kiyosumi, Tokyo.

All images courtesy Naoya Hatakeyama.